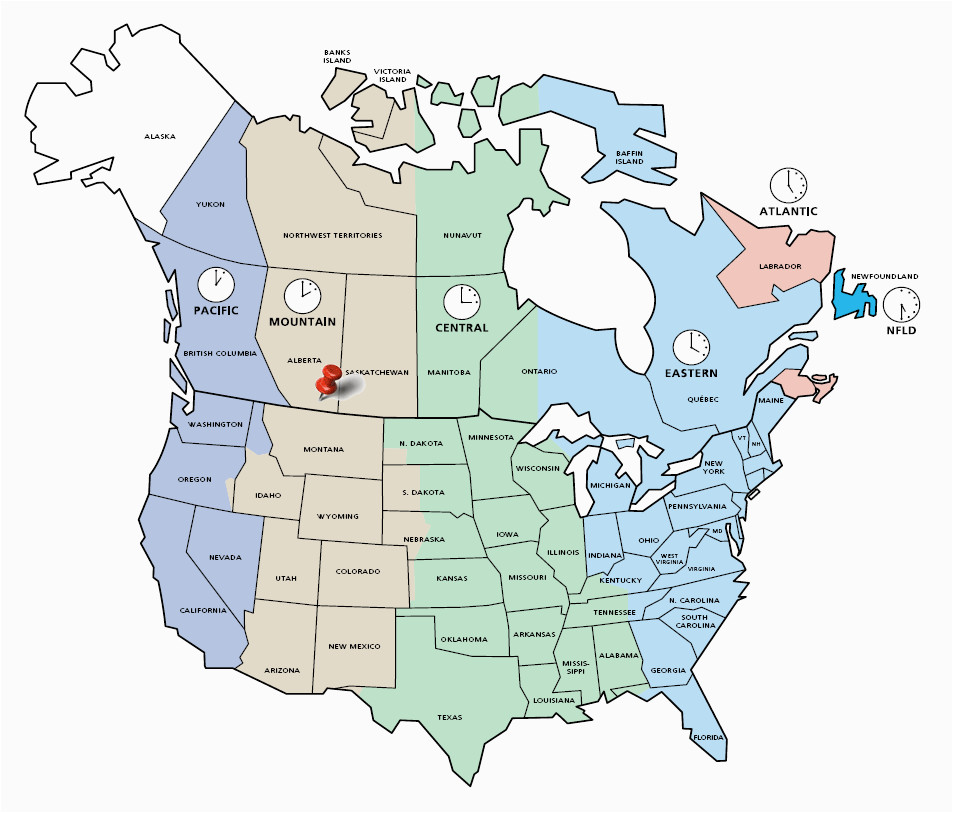

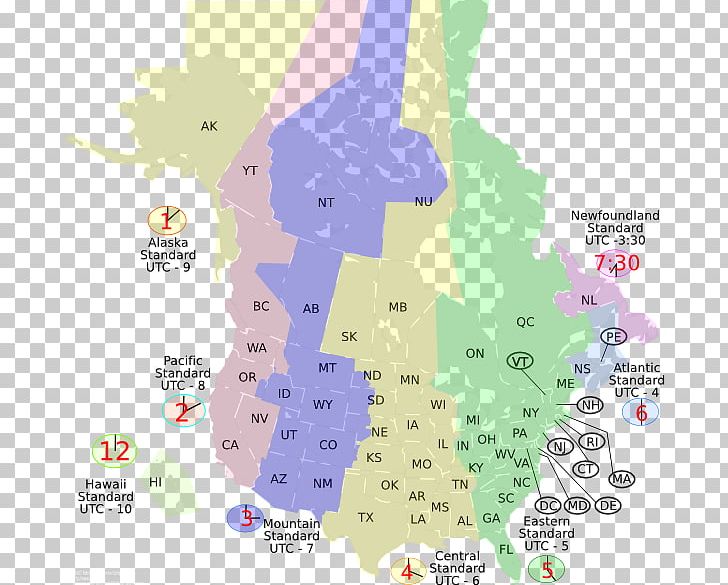

In the 1880s, when trains allowed higher speed travel between these disparate localized time zones, 15-degree longitudinal standard time zones were introduced - in part by Canadian Sir Sandford Fleming - to keep trains running on time, while making sure the times of day still roughly lined up with the sun.īut, in Canada, where a single time zone might stretch across nearly 30 degrees of longitude and over 40 degrees of latitude, people at the western and northern reaches of their time zones are sentenced to a kind of eternal jet lag, their circadian rhythms perpetually at odds with the alarm clocks they set for work and school. “New York’s day started a minute before Newark’s, five minutes before Philadelphia’s, 12 minutes after Boston’s,” writes Clarke Blaise in his book, “Time Lord.” Ditching standard time would make it worse.īefore standardized time, every town was in its own local time zone set to precise solar noon - people woke up with the sun and when it was directly overhead, it was 12 p.m. With everyone across this massive territory waking up around the same time for work and school, many Canadians are left in the dark. EST covers about 60 degrees of latitude before it hits the southernmost point of United States at Key West.

These cities and hamlets are all in the Eastern Standard Time zone, which includes Canada’s most northern point at Cape Columbia, Nunavut and its most southern at Middle Island, Lake Erie. In Grise Fiord, Canada’s most northerly community, the sun won’t rise until 12:12 p.m.

in Toronto 7:51 in Thunder Bay 9:16 in Igloolik, Nunavut, and 10 a.m. On Sunday, most Canadians - except in Yukon, which uses permanent daylight saving and Saskatchewan and other isolated pockets who observe standard time year round - will set their clocks back one hour.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)